I remember the snow-covered rooftop of my childhood schoolhouse; that was during my eleventh December. I wore angels’ wings, plush and purple-white, bound to my back. I focused on the twinkling lights in the distance as I recited the now-familiar verses inspired by Christmas along with the other children. It was all called “Yule Tidings.”

“Now, Go!” My teacher told me with only the gesturing of her hands as she watched me, smiling at me from behind thick glasses crookedly balanced across her nose.“Oh, come all ye,” I sang at her command. I saw no one, heard no one else—only the glistening lights beyond as my eyes watered and fluxed—as my vision came in and out of focus.

In our performance, we trailed across the stage as a group, a flock in our innocence. We performed dutifully as a testament to our faith. We knelt and prayed to a star raised high above us. That star shimmered back unto us, caressing our faces, seemingly in delight. The play’s final highlight—which caused the audience and all of us on stage to clamor—was a baby goat trained to trail across the stage. Our outstretched fingers pushed her forward as she somewhat confusedly abided our guidance.

I watched as she hopped off stage into the arms of another teacher who awaited her in the wings. Ms. Little rocked and cradled her as her bell softly rattled.

The din of my classmates carried me forward as I still was not tasked to use my own eyes and mind. I was taken down a hallway, led by disembodied hands.

“I know why you performed so well,” I heard a voice meant for me. “It was for him.”

I bowed my head at her consideration, and perhaps her solicitude.

When she said, “Him,” I knew who she referenced, and our passing familiarity, along with her natural timidity prevented her from speaking His name. She couldn’t come that close to me. She only gazed down at me. I knew her name, though she was not a teacher of my own.

At the end of the hallway—it was not an impossibly long hallway—I saw an exit door fly open. Its clang prompted me to turn my head. Backlit by the moon and some surveillance lights lining the doorway, snow fell in powdery mounds; some of it shuffled in to dust our feet. Freezing air blew in as well—threatening us.

“Ooh, it’s cold out there. Remember to put on your snow boots. I’ve got to get going.” With that, she placed a knit cap on her head and drew her scarf closer to her throat. When she zipped her coat, I noticed her resemblance to a red-breasted robin, the thick, ripened-red material protruded in esteem. She appeared much more formidable in her winter wear than without; in class, she looked more like a thin, fragile thing who never faced the cold, sun, or anything.

“Bye,” I said quietly as she walked into the veil of snow and disappeared.

I walked out after she left. I wandered out at the sound of a familiar bell—the ting, ting, tinkling of the goat I’d only gotten to touch with a single fingertip. I had strained to touch her from under the mass of similarly-intentioned other students.

Outside, I squinted to scan the parking lot to find her. I moved toward the sound, again, not thinking or wondering where the creature’s owner, Ms. Mittens, could have gone; any interpretation of strangeness in the situation escaped me. I made my way through the newly fallen snow, slid through it so I wouldn’t slip in my patent leather shoes.

I wasn’t completely blinded by the snow. When I finally reached the little goat, I asked her why she was alone. I held her, huddled against the side of the building. Some lights had come on overhead, so I knew someone would see us. My wings shook under the heavy snow. I secured them earlier with crisscrossed straps across my chest. I pulled the creature close to me, feeling its warmth, giving it mine. I drew the top of my wing with a free hand to spread it as well as I could like a blanket.

I looked through my cottony feathers to see only the headlights of cars driving away, going home. When my neck finally began to ache, a close-by door squealed open. I heard, “There you are! And I just thought you up and flew away!”

✴✴✴

Every time July rolls around, I anticipate December; that’s when I see my breath pucker up in condensation as I blow it out into the night. That’s when I can push out a part of me and see it, touch it, poke it with my fingers; and there’s no pain. That’s when I am the night, the air.

In December, the birds fly south, avoiding the bleak, gray skies. Lucky them, they’re able to choose. In December, I move in the cold night, in the cold day, in the cold, cold. That’s when I remember the sherbet skies of July, May, even.

It was my twelfth July; and, the sun was beating down. All I was looking for was water; all I wanted was that and December.

I brought out a glass and set it beside me. I filled it with juice—tart, and sticky. I listened to the ice squeak and jangle. I thought of the word as I deliquesced like everything else around me, wishing I was somewhere else.

I looked up into the orange-tinted sky from behind my sunglasses and all the birds had disappeared. I thought nothing of it as I turned my head to fall asleep, but not to dream. With my eyes closed, my skin moistened, maybe glittering under the blazing sun, I was the Queen of July there all by myself.

At night, my mother told me to go outside and get the mail. The hung moon glowed above with the countenance of a schoolgirl without the blush.

I walked across the grass. As I moved, I considered kicking off my shoes to feel the soft pad directly underfoot. I knew the dirt well, the crumbly, chocolatey mess I dug my toes into—the cool earth.

At the mailbox, I saw a leaf, large and marbled in a shade of green, or brown I’d never seen. I grazed a part of the leaf with my foot as I tiptoed off the grass to get the mail. At my touch, the papery-thin leaf’s color coalesced into shades of bright green and purple under the streetlight. I watched as the leaf folded like paper; it moved on its own. I backed away to view the thing properly. Now, there were two purple leaves joined at some point I couldn’t see. Before my eyes, the leaves spread apart and bound off into the night.

✴✴✴

At the beach with my mother and the strawberry-colored sky floated above me. I was a fish in a fishbowl. Pretending to panhandle, I combed the soft, slimy sand between my pudgy, brown fingers.

“All I have is time,” my mother said as she lay reading in the distance. Her strong body, her frame in a red bathing suit, was only a black speck from far away. I pointed at her, but she couldn’t see me. I blotted her out with the tip of my finger; I was that powerful. Alone, she sighed.

Birds flew above us all; there were only a few of us out that day. The crashing waves beckoned me with longing. I put a toe in the burning cold water. I went in.

Afraid of the invisible beings that may creep underfoot, my toes curled at the touch of the rocks and shells. I closed my eyes as a bird cried overhead. It was either the bird or its prey.

I didn’t want to get the water into my mouth. I was afraid of the salt, the burn of the taste. I let the water splash against me knowing that the water was like the fluid running through my own body, running like a life-giving thing; I was at home.

I was nearly asleep when my mother called out to me. She waved and shouted, “Come on, girl!”

I went to her and saw the food she had brought for us. I ate a tuna sandwich and drank water. “Careful, now,” she told me as I chugged along.

“Hasn’t this been a nice day?” Mother asked me. “And there’s not too many people out, today.” She held her belly as it protruded, full with her next child.

“I don’t know. There’s been no one to play with.” I frowned.

“I thought you’d enjoy some alone time out here. It’s a nice change of scenery if anything else. You may not have noticed, but you’ve been sticking to yourself lately.”

“I just like to be alone, now.”

“And, you’ve been having upset stomachs and things. You know what I think it is. You’re at the right age.”

I bowed my head. Turning away from my mother, I ate my sandwich.

“It’s a wonderful thing to be able to give life, you know. Just wonderful.” My mother spoke to me, though she couldn’t see my face; and I didn’t want to see hers. “Humph. Just at that age, I guess.”

✴✴✴

Our schoolhouse sat in the middle of outstretched land that was, otherwise, empty. We’d run outside with nothing to break our pace, frolicking freely. In July, the onion patch, the dust, and the air unseen stung my nose in the heat. Summer school stung me worse than the smell of all that, though.

I rode the bus with the other noisy children; fortuitously, I was always allowed to sit alone. I’d look outside to see the sky, the clouds trailing alongside and after me, filling me with contentment by virtue of only their fluffy looks. That’s where the birds fly.

Below them, I saw two dogs coming to each other, moving slowly against the speed of the bus. The teeth of one of the dogs raged out as he barked at his opponent. One dog was brown, the other black with a short tail.

When they met, they brawled. On the bus, the children screamed; the bus driver yelled into the air, “Well, don’t look at those dogs!”

There was blood as the winner limped off only to lie down and die at the edge of the road. Those birds that previously flew above us in serenity landed to feast. I was the only one left watching, left alone to digest the final outcome.

The bus drove off, drove me home; it ejected, then deposited me beside the mailbox. I stood in the grass looking above. I waited for the birds, but none appeared. My dog came to me and sniffed me up and down.

“You want to know what I’ve been doing?” I asked. He smelled something on me, something new; I wondered if he could smell the contents of my mind. Each new day at school bore something new within me.

✴✴✴

In our sunlit classroom, the air was sweet and bitter at the same time; it was sweet because of the plaster, or something sprayed into the air—because of some cleanser used to wipe the vomit a boy named Lester put on the floor just that morning.

The bitterness came from something else, something foreboding. As our teacher with her chalk-stained hands and ripped stockings moved across the room, I drank that air, swallowed it, and waited.

Having been in that seat since morning, I was restless. I looked over at my neighbor to see him pull the glue—pasty and minty—out of his desk compartment and taste a bit of it. I scrunched my nose at him to tell him what I thought of his actions. He only smiled; and no, that wasn’t Lester.

I heard the scratching of the chalk against the blackboard, a snap, and, “Damn,” whispered away from us. Ms. Mittens looked behind her to see if one of us had caught that. I lowered my eyes to make sure she didn’t notice me.

Clearing her throat, she said, “Notice how the uppercase cursive letter “B” resembles a butterfly’s wing. Lovely. Remember that as you practice your signatures; you don’t want to make them illegible.”

I looked down at what I had scribbled down onto the paper. I was practicing how I would sign my name quickly. “Brevity matters,” our teacher said. “Do it quick in case you’re in a hurry somewhere. It’s just a quick mark; but, make sure you can do it the same way every time you sign it. And, above all else, make sure it’s legible.”

The signatures I have seen came into my mental view; I remembered my mother’s, my father’s, and my grandmother’s marks. My father’s signature was the worst as it was only a scratched letter “M.” He never got past the “Mr.”

I looked at my own signature and decided to match his “M” with my own. I made mine squigglier though; and, as a sign of my girlishness, I added a heart above it. “Images,” I thought.

Feeling the heat of a stare, I looked up and directly across from me and saw Rita glaring. She was mad; I guessed she was mad at me.

Realizing my fear of her, Rita mouthed, “Meet me outside after class. I’m gonna jump you!” Immediately, I planned how I’d avoid the main exit door at the end of the day.

“Now, Rita. Try to pay attention to what you are doing. You can talk to your friends later,” Our teacher—my only hope of protection—spoke with her hands on her hips. “The day’s almost over. Please control yourself.”

Rita, wild and typically enraged at everyone, seemed to semi-cool it; she slumped back down in her chair. I could never meet her eyes. That’s how she knew I was afraid of her. To me, my fear of her was inexplicable, yet ever-present.

✴✴✴

It was the end of Monday; like clockwork, I had to go to the bathroom. Ms. Mittens permitted me to go. Bypassing Rita, I took the wooden pass marked “G” in red ink and ambled out the door.

I remember the hallways, the blueness of them—blue-plastered walls, blue-and-white-checkered floor tiles. The musky, pre-pubescent odor of sweat was unnoticeable until I exited into the kindergarteners’ hallway—the yellow hallway. Crossing the halls from blue to yellow was like walking a path from night to day; it was safe and clean in the (yellow) kiddie hall. There, the depiction of a swan in flight was pictured across the wall as a mural. The swan grew and its image was staggered across the wall.

I took a few moments to admire the twinkle in the bird’s eye as it stared sideways at me, never turning its head. The swan faithfully remained on its course all the way up to the beginning of the hallway, right at the kindergarten teacher, Ms. Nesbit’s, door. I wasn’t going that far, though. The children putting away their toys, dropping them clumsily, the whack and deadened jingle bell as Jack-in-the-Box was dropped upon his head, made me take pause.

I listened before opening the bathroom door. I preferred the bathrooms in that yellow hall, always clean and looked after by our pudgy janitor. Though they seemed smaller, somehow, I could still fit in there. I went in and sat on the toilet and relaxed; this was a thing I could only accomplish in the yellow bathroom. Rita wasn’t coming into that bathroom. I sat there with my elbow on my knee, resting my chin in my palm.

At hour’s end, thankfully no one had come to look for me. The final bell rang; the crash and bang of children catapulting out of their classrooms into freedom did not deter me. I held my position firmly atop that toilet.

When the surging pulse of the day’s end was over, I relaxed again. With an unexpected force, the bathroom door swung open; but that force was misleading. The entrant made her way into the stall beside me on light, fast-paced feet; a kindergartener?

I looked at the wall between us, listening. She was just as curious about me; when I found the floor beside my feet, I saw her pig-tailed head duck under and in my stall. She said nothing; with large eyes, she was gone in a flash.

I didn’t speak or call after her. There was only immediate, harried contemplation of what I could say to anyone to explain what I was doing there after school in that bathroom that wasn’t for me sitting with my legs spread over the toilet seat. Oh, she’d surely tell.

It could’ve been the worry and shame; it could’ve been on its way to me all day, all month. Just as sure as I can sometimes feel the beating of my heart, I felt a watery whoosh from the center of my chest down to my groin. It was a molten, flowing stream that had been dormant until some strange event of the day. Some natural change within me woke it up.

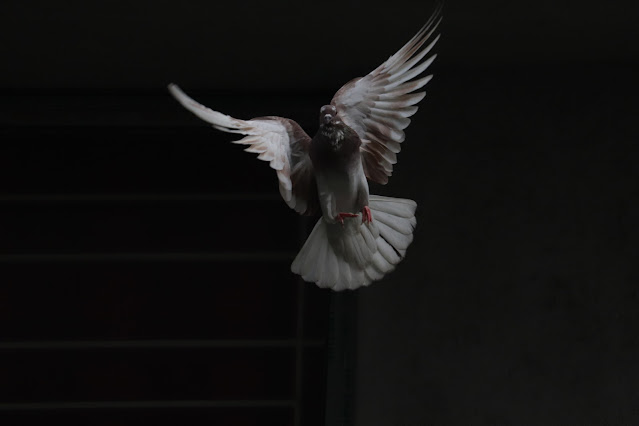

I lifted my plaid skirt up as I felt a ball, round yet not fully formed, appear at the base between my legs. There was a short thud of pain. I looked down not wholeheartedly wanting to see the blood, and there was no reaction. I only gazed at it—a dove or some other white bird had escaped me in that bathroom stall. I was neither pleased nor disgraced. The creature flew, as such animals do, raucously crashing into the stall and throwing itself upward. I turned my whole head to see it. My eyes grew large.

I could only see as far as the stall’s limits, so I finally left that place without fear. The white bird I had only just birthed crashed against the window—its last obstacle. I opened the window and watched as it flew toward the sun.

✴✴✴

0 Comments